Nightmare Scenario

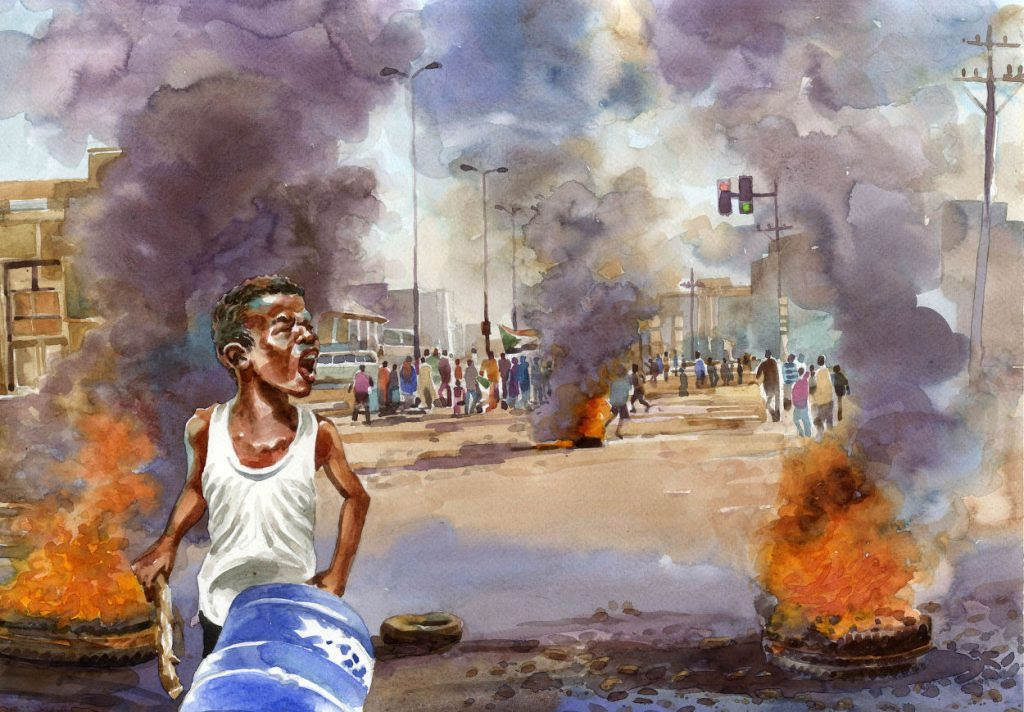

After the horrible fall of El Fasher in Sudan’s Darfur region, media and online ecosystems have at last given mainstream attention to the civil war that has embroiled the country for over two and a half years. The accounts of the indiscriminate killing and raping that have been spilling out of the city of refugees have deeply shocked the world’s conscience, brute-forcing this “forgotten war’s” irrelevancy back into the public eye. Indeed, the ongoing atrocities are near-unimaginable. Thousands upon thousands of civilians have been murdered, and so much blood has been spilt that it can literally be seen from outer space.1

The takeover of El-Fasher by the Rapid Support Forces and the subsequent ethnic cleansing and acts of genocide, though shocking, have not nearly been unpredictable by those who have been following the conflict. The city itself had been subject to an eighteen-month-long siege before the Sudanese military finally withdrew in late October, and experts had long predicted that the hundreds of thousands of refugees that had fled from other parts of the region would be made the target of a campaign of annihilation. What is most tragic is that this war has continued to churn on, with little resistance from the international community to understand or campaign against this conflict.

I write this article to an audience of those who are pro-peace and anti-imperialist, who wish to understand this conflict with the same rigor and scrutiny. I write particularly to those in the Palestinian solidarity movement, whom I have seen often acknowledge this conflict by linking it to similar genocides in Palestine and the D.R. Congo. My hope is that this essay provides a deeper and more thorough analysis than those from mainstream sources, which, in my experience, have often been reductionist, overly-simplified, and racist.

I first provide a brief overview of the timeline of the current Sudanese civil war (there have been at least three since the country’s founding), which began in April 2023, providing some facts and figures that demonstrate the intensity of this ongoing conflict, and why it demands our attention. Then, I show that understanding the history of Sudan through an anti-imperialist and anti-colonial lens reveals historical patterns of dominance and exploitation that remain central to this conflict and, more importantly, the key to its absolution. I hope that those who read this article will have more informed and nuanced methods of interpretation to this war which, on the surface, remains inscrutable to the West. Of course, those in the Palestine solidarity movement have heard this line time and again (“it’s such a complicated history!”), and will find that the very methods of analysis that we have sharpened, particularly over the last two years, and applied to Palestine/Israel are again relevant for this civil war which has long escaped our deserved attention.

Origins of Current Conflict

In 2019, the longstanding dictatorship in Sudan headed by Omar al-Bashir was overthrown in a process that began with a sustained non-violent civil disobedience campaign led by civilian forces and that culminated in a coup-d’etat by Bashir’s own security forces.2 A joint civilian-military transitional council was implemented, with the promise of a full transition to a civilian-led democratic government within 39 months. Two years after this, however, the Sudanese military wrested control of Khartoum in its entirety, detaining the civilian prime minister and dissolving the state’s Transitional Security Council.3

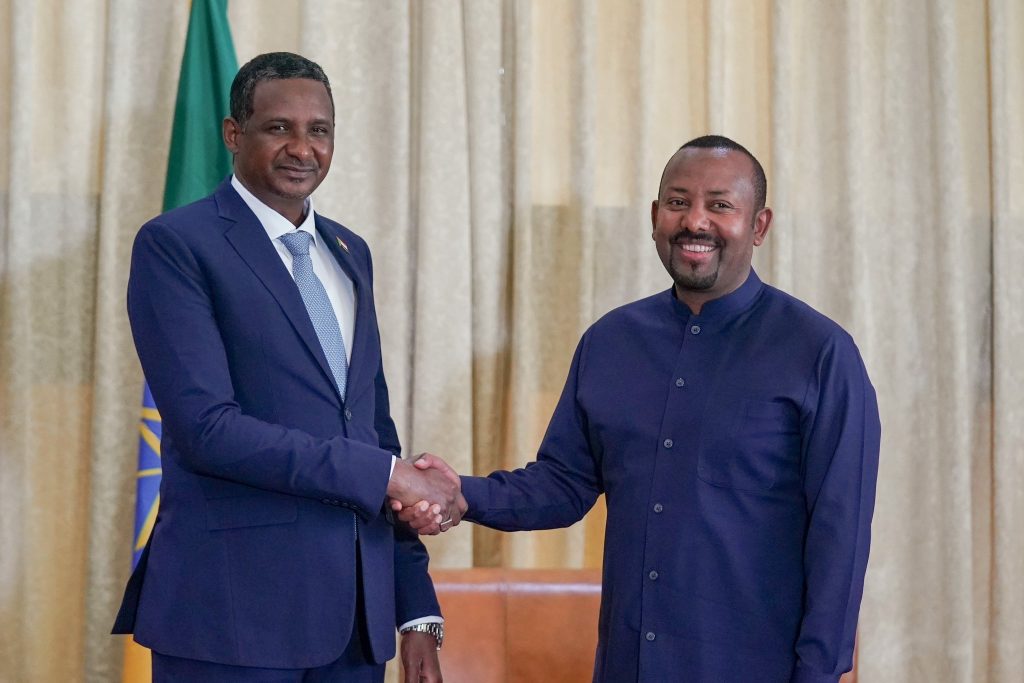

Throughout all of this, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), headed by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, was assisted by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a military wing led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, most commonly known as “Hemedti.” The RSF has its origins in paramilitary groups that the army had paid in prior conflicts, most notably the Darfur conflict in the early twenty-first century; these groups were colloquially called the Janjaweed. In 2014, in order to secure more control over the group, the Janjaweed was formally consolidated into the RSF as an official arm of the military.4 After the 2021 coup, al-Burhan pushed to further integrate the RSF into the military. Hemedti recognized that this closer SAF-RSF integration would dilute his power and put him in a subordinate military position.5 In response to this move, Hemedti and his forces launched a major attack against SAF bases and strongholds in Khartoum in April 2023. This attack is recognized to be the start of the current conflict that is ongoing. Since then, the civil war between these two military factions has spread to most regions of Sudan, with the bulk of the fighting occurring in north/central Sudan (Khartoum), west Sudan (Darfur states), and southeastern Sudan (the states along the Nile River, including the White Nile, Blue Nile, and Gezira).

Two and a half years of this conflict has created one of, if not the largest humanitarian crises in the world. The UN Refugee Agency estimates that over 13 million civilians have been displaced, many of them fleeing to neighboring countries like Chad, Egypt, and South Sudan; nine million are internally displaced within Sudan.6 Calculating the number of casualties in this conflict is incredibly difficult, as on-the-ground information is hard to come by, but estimates put this number at around 30,000 directly killed by the conflict, which include about 7,500 civilian casualties.7 Both the RSF and SAF, according to a UN fact-finding mission, are complicit in an appalling range of human rights violations and war crimes.8 The two sides have attacked civilians and civilian infrastructure indiscriminately and intentionally. Both have also used arbitrarily arrested and tortured civilians suspected of collaboration with the other side.9 And both have used sexual violence as a weapon of war; the RSF particularly, which has committed near-countless instances of mass rape, gang-rape, and sexual slavery through their conquest into the Darfur region.10 This sexual violence by the RSF in Darfur has been accompanied by the targeted executions of civilians from the Masalit ethnic tribe11––an intentional campaign that many have explicitly labeled a genocide.12 This includes former US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken (yes, the irony should be lost on no one).13

The wartime conditions, including the international blocking of humanitarian aid and the use of siege warfare on cities and camps, have led to a complete collapse of healthcare infrastructure.14 It has also created one of the largest man-made famines in the twenty-first century, with over 750,000 people facing what the UN’s Famine Review Committee describes as “catastrophic conditions”.15 Children are particularly vulnerable, with over 7 million without access to safe drinking water, according to the WHO.16 Not only has humanitarian aid been blocked and denied by the warring parties, but most agencies recognize the international response to this crisis as woefully inadequate. For example, only 57% of necessary funds for the Sudan Humanitarian Funds and Response Plan was received in 2024. This itself was an increase in funding from the year prior.17 Sudan, it seems, has once again in its history been relegated to a “forgotten conflict,” particularly in the Western world, as it rages on and in fact shows signs of intensifying after over two and a half years of bloodshed, displacement, erasure, genocide, and catastrophe.

Sudan’s Colonial Legacy

The ongoing civil war between the SAF/al-Burhan’s forces and the RSF/Hemedti’s forces across Sudan seems to have a simple, surface-level narrative: the two military leaders are both vying for control over the state of Sudan. The genocide in Darfur is also seen by much of the mainstream press as a relatively straightforward instance of deeply-rooted tribal conflicts escalating to eliminationist extremes. However, any rigorous anti-imperialist should be sceptical of this straightforward explanation, which seems to rely heavily on racist caricatures of backward African states unable to cooperate or exist in peace. In actuality, the current conflict is ultimately an extension and intensification of an ongoing Sudanese state-building project, one that is both rooted in economic, political, and cultural marginalization of peripheral states, as well as by dominance and coercion from foreign actors. These systems of exploitation are by-and-large structures of coloniality. In this way, to understand the conflict in Sudan, it is necessary to understand the impacts that colonization has had, and continues to have, on the region.

I am not arguing that the states of Sudan were a utopian paradise prior to colonization, where all peoples lived in perfect harmony––far from it. Nor do I believe in a reductive way that every problem in Sudan is downstream of colonialism. Rather, we should aim to recognize that many of the contemporary economic, social, and political relations taken for granted as “the way things are and always have been” in Sudan were, in fact, largely constructed, solidified, and reified during the colonial era. These relations have seen further mutation and transformation since the transition of power from colonial governors to local elites, as well as the turn to a neoliberal, transnational economic mode of production. They remain central to the organizing structure of the state, and thus its triggers for conflict and instability.

The racialization of ethnic tribes is among the most distinct ways in which coloniality is made manifest in Sudan’s state formation. Since the war in Darfur in 2003, Western media has produced a binary view of relations in that region: there are “indigenous” farming African tribes, also known as Zurqa, and “settler-invader” nomadic Arab tribes.18 This narrative continues to dominate––a very quick peruse in The New York Times will find that the paper identifies the RSF as “mostly ethnic Arabs.”19 This conception is actually dated far back to the very first ethnographic studies and travelogues to emerge from the region by British and French explorers hundreds of years ago.20 This type of value-laden categorization is, of course, never neutral; rather, it has always been weaponized to fragment, exclude, and ultimately control populations, to the benefit of colonial powers and the elite ruling class.

Prior to the colonial conquest of Sudan in the late nineteenth century by Britain and Egypt, tribal affiliation was perceived as fluid, evolving, and in symbiotic relationships with each other. Ethnic and tribal groups in Darfur, regardless of their coding as Arab or African, Fur or Masalit, have been and are functionally identical to each other in terms of pigmentation and physical features. This is because of centuries of intermarriage between these different groups.21 Tribal affiliation, prior to colonization, was seen as more socially- and locationally-contingent. There were periods where nomadic groups would adopt an agricultural lifestyle and “become” members of another ethnic group, and vice versa.22 The relations between nomadic and farming groups were symbiotic, and the two would help each other survive collectively. In contrast to this vision, several centuries of British historiography have reified the idea that the Arab groups are more “light-skinned” than their African counterparts. A racial hierarchy emerged––one that justified the domination of “African” tribal groups (the ones usually on the fringes of the colony/state) by “Arabs,” who, while not as humanized and “pure” as the white race, were nonetheless higher in the racial pecking order.

Beginning with the colonial domination of the Anglo-Egyptian condominium, and extending during the invasion of Darfur in 1916, a new bourgeois class in the central region of Khartoum/Omdurman began to internalize the racial hierarchy of Arab/African. 23This kind of identity divide has provided justification and legitimization––what’s often described as “cultural violence”––for the marginalization of the western (Darfur and Kordofan) and southern (South Sudan and the Nuba Mountains) regions of Sudan. This very racial logic became an easy scapegoat explanation that the Khartoum government could turn to in the wake of mass atrocities and violence against civilians in Darfur perpetuated by the Janjaweed paramilitaries that the government was funding. The violence could be excused of any kind of centralized blame, owing to its supposed “ethnic” and “deep-rooted nature”.24 This reductive interpretation ignores the confluence of factors that led to the horrible bloodbath in Darfur from 2003-05: the formation of the Janjaweed includes decades of Libyan and Chadian militias entering the region and flooding it with arms, a famine in the eighties that decimated the livelihoods of many nomadic communities and created a refugee crisis, marginalization that created a class of young men desperate for money and a way out of the region, and, of course, the adoption of an “Arab” identity of certain tribal groups. In Darfur, this Arab identity was not even present until just a few decades ago (in the nineties), and it was opportunistically seized upon and amplified by Khartoum.25 All of this history is flattened, by the Sudanese government, by Western media, into “a conflict between Africans and Arabs.”

The economic and political structures that underpin the modern relationships in Sudan can be largely traced back to Sudan’s position within the British empire. The Gezira Scheme is one such example. In 1900, cotton accounted for less than 5% of Sudan’s national exports.26 By 1950, less than five decades, this cash crop shot to as high as 80% of total exports. This transition massively shifted farming and food production away from internal subsistence and towards exportation to the empire. The same economic shifts could be traced to cattle sales in Darfur. These reorientations increased the economic value of Sudan for their imperial overlords, but not for Sudanese.27 This economic development can be contrasted against the explicit underdevelopment of many other sectors, including in health and education.28 When education was established, it was relegated exclusively to a class of elites, usually in central Sudan. When educational opportunity was extended to the regions of Darfur during the late colonial period, attendance was limited exclusively to the sons of local chiefs. Even here, the Darfuri students were explicitly taught to accept a subordinate role in both the Sudanese colony and a later-to-be-independent Sudan.29

When Sudan entered its period of decolonization in the 1950s, rather than a complete transformation of the system, the dependencies and core-periphery relationships simply transferred from the hands of elites abroad to elites at home. The racialization that was internalized onto a specific group of tribes that began to identify themselves as “Arab” saw little issue with continuing with a synthesized western/Islamic notion of “development” onto the peripheral African/non-Muslim states. Many of the states in Sudan, including South Sudan, Darfur, and the Nuba Mountains, became effectively an “internal colony.” This is reflected in the economic and political makeup of the country today. Since its independence, oil exploration and dam construction has been intensified. All of these massive economic projects sought to expropriate the natural resources and wealth found in Sudan’s territory, which caused mass displacement and the destruction of livelihoods.30

Political representation and power rests almost exclusively in the hands of a tiny minority of ethnic groups, all of them from the north. This was elucidated succinctly in The Black Book, a document written by activists and distributed in several Sudanese regions in early 2000. This document, which was signed anonymously by “Seekers of Truth and Justice,” uses statistics and data to demonstrate the inequalities of the executive powers, legislative and judicial authorities, and media control. The text was central to the establishment of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), one of the primary fighting forces in the Darfur war, as well as other secular resistance movements, which were founded just a few years after The Black Book was published. The JEM’s popularity in Darfur demonstrates that political and economic marginalization was what was foremost on the minds of rebels and resistance fighters who chose to take up arms against the state, rather than an ethnic/tribal motivation, as is frequently implied by Western press and is an advantageous position from the Khartoum government.31

Coloniality has been made manifest in Sudan in many ways, structuring its epistemologies and ontologies, and assigning hierarchies based on skin tone and ethnicity that justify the dehumanization of some groups over others. It concentrates political and economic power into a minuscule group at the top. And this tiny elite is able to exploit the resources and labor power of those on the bottom, the peripheral states, whose economies have been reoriented and set up to be as fruitful and generative as possible to the core. This process, though far from linear, has taken on multiple mutations and transformations over the last century and a half. Properly contextualizing this history is essential for identifying and articulating paths that will create a true, sustainable peace in Sudan’s future.

Outside of this, one must also account for the foreign dominance and exploitation of Sudan and its resources, with external actors funding, arming, and pushing the conflict to its bloody extremes for access to Sudan’s abundant materials. The UAE, in particular, has perhaps been the only reason why the RSF is able to continue to arm and resupply itself, making the Gulf country “complicit in genocide,” much like the US’s role in supplying and providing support to the Israeli campaign of genocide in Gaza.32 It has even gone as far as to send mercenaries from Nigeria and Colombia into the country to fight with the RSF.33 This is linked to the RSF’s control of important gold reserves, and this precious metal is often smuggled out to Chad or Libya to be exported to the UAE, as a recent Swissaid report found.34 Before the war, most gold from Sudan was exported to the UAE, but since the start of the conflict, the Sudanese army has shifted their control of the gold market away from the Gulf states and towards Egypt, who remains the largest financial supporter of the SAF. The scramble for gold and other agricultural resources has been a primary driver of the continual funding of this conflict, as resources like oil have been in Sudan’s conflicts in the past. It is impossible to reduce this conflict to an entirely internal affair, just as it is impossible to untangle Western complicity from Palestine/Israel. The civil war and genocide need to be understood as a complex and cynical proxy struggle, primarily between the Emiraties and Egypt, but with Russia, Ethiopia, Israel, and other regional states standing to gain from the rise or fall of either the RSF or SAF. Caught between this grand and brutal international struggle are the Sudanese civilians, who remain stripped of their dignity, value, and voice.

Conclusion

Sudan has been among the most conflict-prone regions in the world for decades. These instances of direct violence are emblematic of the deep structural and cultural violence that has constructed the nation-state as it exists today. Any form of peacebuilding that lacks this historical knowledge, this analysis on the material structures that have shaped and continue to shape relations of exploitation and domination in the modern day, will ultimately fail in its endeavor to establish a true, lasting peace. A truly sustainable peace requires the restructuring of these economic, cultural, and political apparatuses that continue to marginalize and make conflict inevitable. This requires moral courage, historical honesty, and a commitment to accompany, not to walk ahead of, the people of Sudan in their struggle for liberation, sovereignty, and peace. Sudan’s future is at a critical crossroads; the path it will take is uncertain in the fog of war. As hard as it is to hear, this war will likely get worse before it gets better.

To those who are just becoming aware of this conflict for the first time, or who are finally taking a deeper look at this long and bloody war, I encourage you to use this article as an intellectual launching pad, to keep investigating further, and to keep applying the same rigor and orientation that those of us in anti-imperialist spaces have applied in other conflicts. I hope that Sudan, like far, far too many atrocities in the Global South, does not become a “forgotten war”. I hope that the dignity of the Sudanese people, especially those in Darfur, are rightfully restored, that their history is properly contextualized, and that we all commit ourselves in this protracted and bitter fight against colonialism and imperial powers so that peace and justice replace this nightmare unfolding in our midst.

- Sudan War Monitor, “Thousands killed and others escape in chaotic rout of El Fasher defenders,” Sudan War Monitor, October 29, 2025, https://sudanwarmonitor.com/p/fall-of-el-fasher. ↩︎

- Mai Hassan and Ahmed Kodouda, “Sudan’s Uprising: The Fall of a Dictator,” Journal of Democracy 30, no. 4 (2019): 89–103, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0071. ↩︎

- Jason Burke,”Sudan Coup Fears Amid Claims Military Have Arrested Senior Government Officials,” The Guardian, October 25, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/oct/25/sudan-coup-fears-amid-claims-military-have-arrested-senior-government-officials. ↩︎

- Sudan Tribune,”Sudan Army to Accept Ceasefire Deal with Mediators’ Amendments: Sources,” April 24, 2024, https://sudantribune.com/article270946/. ↩︎

- Abdelkhalig Shaib, “Sudan’s Transitional Process Is Dead and Buried,” Arab Center Washington DC, April 17, 2024, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/sudans-transitional-process-is-dead-and-buried/. ↩︎

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR),”Sudan Situation,” accessed April 27, 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/sudansituation. ↩︎- Warren Cornwall, “How Many Have Died in Sudan’s Civil War? Satellite Images and Models Offer Clues, ” Science, April 11, 2024, https://www.science.org/content/article/how-many-have-died-sudan-s-civil-war-satellite-images-and-models-offer-cl ues. ↩︎

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “Sudan: UN Fact-Finding Mission Outlines Extensive Human Rights Violations, ” September 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/09/sudan-un-fact-finding-mission-outlines-extensive-human-rights-violations. ↩︎

- Sudan War Monitor, “Mass Arrests in El Fasher after Military Suffers Setback, ” April 2025, https://sudanwarmonitor.com/p/mass-arrests-in-el-fasher-after-military-suffers-setback ↩︎

- Amnesty International, “Sudan: Rapid Support Forces’ Horrific and Widespread Use of Sexual Violence Leaves Lives in Tatters, ” April 18, 2025, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/04/sudan-rapid-support-forces-horrific-and-widespread-use-of-sexual- violence-leaves-lives-in-tatters/. ↩︎

- Maggie Michael and Emma Rumney, “Special Report: In Sudan, Signs of Genocide Emerge in Darfur, ” Reuters, March 5, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/sudan-politics-darfur/. ↩︎

- https://abcnews.go.com/International/blood-visible-space-sudan-shows-evidence-darfur-genocide/story?id=1269855 ↩︎

- U.S. Department of State, “Genocide Determination in Sudan and Imposing Accountability Measures, ” December 6, 2024, https://2021-2025.state.gov/genocide-determination-in-sudan-and-imposing-accountability-measures/. ↩︎

- Alhadi Khogali and Anmar Homeida, “Impact of the 2023 armed conflict on Sudan’s healthcare system. ” Public Health Chall. 2023;2:e134, https://doi.org/10.1002/puh2.134. ↩︎

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), “Famine Confirmed in Sudan’s North Darfur, Confirming UN Agencies’ Worst Fears, ” April 18, 2025, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/famine-confirmed-sudans-north-darfur-confirming-un-agencies-worst-fears. ↩︎

- UN News, “Sudan: Thousands More Flee as Darfur Violence Worsens, ” January 18, 2024, https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/01/1145882. ↩︎

- Concern Worldwide, “Lack of Funding Leaves Humanitarians Struggling to Respond to Deepening Crisis in Sudan, ” April 18, 2025, https://www.concern.net/press-releases/lack-funding-leaves-humanitarians-struggling-respond-deepening-crisis-suda n. ↩︎

- Gruley, “The evolving narrative of the Darfur conflict as represented in The New York Times and The Washington Post, 2003–2009. ” ↩︎

- Abdi Latif Dahir, “How Sudan’s Capital Was Torn Apart by Civil War, ” The New York Times, April 24, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/article/sudan-khartoum-military.html. ↩︎

- Rogaia Mustafa Abusharaf, Darfur Allegory, University of Chicago Press, 2021. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Alex De Waal, “Who Are the Darfurians? Arab and African Identities, Violence and External Engagement, ” African Affairs 104, no. 415 (2005): 181–205, https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adi035. ↩︎

- Abusharif, Darfur Allegory ↩︎

- Gruley, “The evolving narrative of the Darfur conflict as represented in The New York Times and The Washington Post, 2003–2009. ” ↩︎

- Flint & de Waal, Darfur: A Short History of a Long War ↩︎

- Mollan and Corker, “Sovereignty and Imperialism. ” ↩︎

- Vaughan, “Late Colonialism in Darfur. ” ↩︎

- Elmukashfi, “The Role of Colonial Powers in African Conflicts. ” ↩︎

- Vaughan, “Late Colonialism in Darfur. ” ↩︎

- Wise, “Genocide in Sudan as Colonial Ecology. ” ↩︎

- El-Tom, The Black Book. ↩︎

- https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/04/1162066 ↩︎

- “Is the Sudan War really ‘about nothing’?, ” The Continent, Issue 209, August 16, 2025. ↩︎

- https://www.swissaid.ch/en/media/united-arab-emirates-more-than-ever-a-hub-for-conflict-gold/ ↩︎